On 12 September 2019, our Training Director, Professor Joel Lee, published a blog post on the Kluwer Mediation Blog entitled "A Neuro-Linguist's Toolbox - Self-Care and Improvement: Preliminary Thoughts". His blog post is reproduced in full below.

A Brief Recap

I have been looking into matters of self-care and personal improvement for mediators recently and was surprised to find that, even though there has been some writing on this, there isn’t a lot. So, I would like to focus my next section of blog entries in the “Neuro-Linguist’s Toolbox” series.

For readers who are new, the “Neuro-Linguist’s Toolbox” series is an ongoing series focused on using Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) in our practice of amicable dispute resolution. The first section (with 6 entries) focused on rapport

1. A Neuro-Linguist’s Toolbox – A Starting Point and Building Rapport

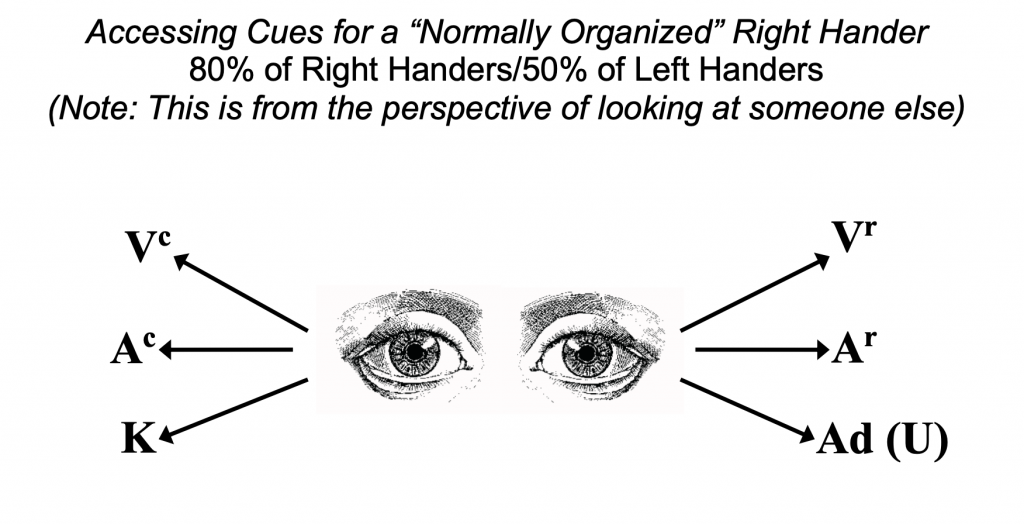

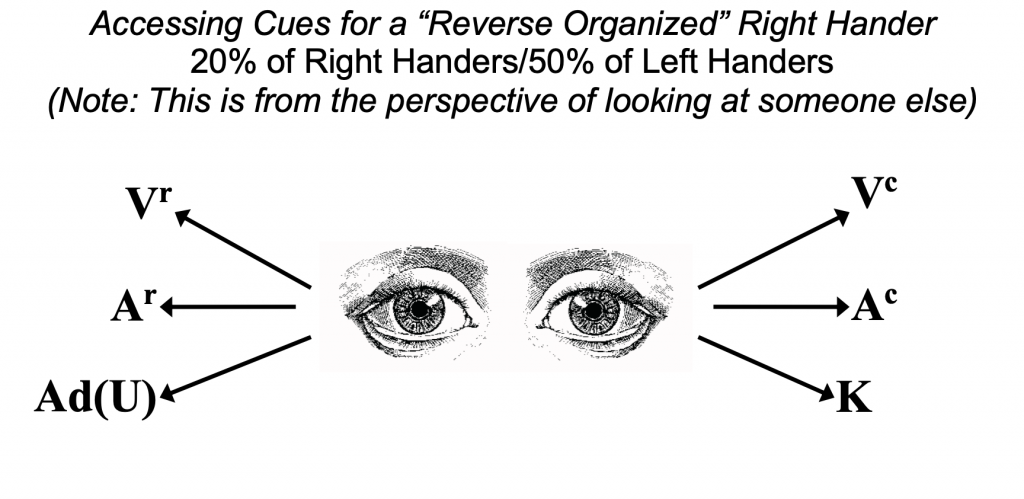

2. A Neuro-Linguist’s Toolbox – Rapport: Non-Verbal Behaviours

3. A Neuro-Linguist’s Toolbox – Rapport: Representational Systems (Part 1)

4. A Neuro-Linguist’s Toolbox – Rapport: Representational Systems (Part 2)

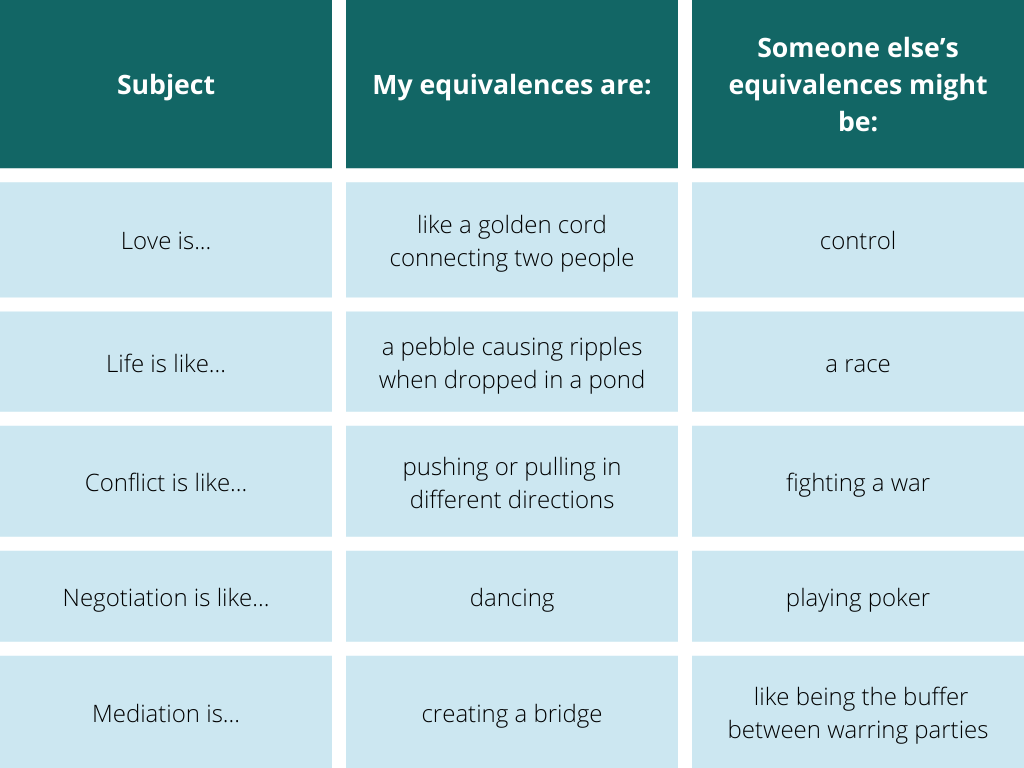

5. A Neuro-Linguist’s Toolbox – Rapport: Values

6. A Neuro-Linguist’s Toolbox – Rapport: Metaphors

Now that the preliminaries are out of the way, onward to self-care and improvement. It is trite, or at least it should be, that as mediators, self-care and improvement should be an important part of our practice. I say this for three reasons.

Self-Care and Improvement

First, as mediators, we are constantly exposed to conflict and have to deal with strong emotions and high levels of stress, not just the parties but our own. This is in addition to whatever conflicts, emotions and stresses that we have to deal with in the other contexts of our own lives. And while some of us can dissociate and keep the contexts separate, the reality of it is that these build up and leak between contexts.

How many of you feel exhausted at the end of a particularly intense mediation? In the medical community, there is the anecdotal phenomena of some nurses and doctors manifesting the symptoms of their patients. There are similar reports in therapy and counselling and this is often associated with burnout and PTSD. If this is accurate, then there is every reason to expect that the conflicts, emotions and stresses associated with our mediation work can leak into and shade the other contexts of our lives.

Secondly, as mediators, we are often unconscious behavioural models for parties. How we approach conflict, manage emotions and deal with stresses can significantly influence how parties behave in a mediation. So, it is important that we be in the best state we can be in when starting a mediation and maintain the best ongoing state as the mediation progresses.

Finally, as a matter of practice, it is often good to reflect upon what we did well during the course of the mediation and what did not go as gloriously. The key, of course, is to positively reinforce the things we did well and to identify what could have been done differently, with a view to improvement. Life of course, is not always this easy.

Sometimes, what gets in the way of good reflective practice are our personal demons, insecurities and emotions. As a result of some bad experiences, some mediators experience identity quakes about their abilities to mediate well. Others may feel strong negative emotions in dealing with conflict or certain types of parties. These will impair our performance and our ability to learn and develop.

Some Reflections

There is an internet meme (I know others disagree but I feel there is a lot of wisdom on the internet!)

As people helpers, if we do not find some way to take care of ourselves, we are no good to the people we are supposed to help.

I remember a visit to the Samadhan Mediation Centre when I was in New Delhi for a conference on mediation. As we were shown around the facilities, we came across a room, curiously labeled “Meditation Room”. Initially I thought it was a misspelling of “Mediation Room”. However, upon clarification, we were told that the room was for the Samadhan Mediation Centre’s mediators to meditate; before and/or after their mediation session.

While meditation does take on connotations of mental voyages and in some cultures mysticism, if we look at this simply as spending time alone, and sorting out and coming to terms with one’s own thoughts and emotions, then the self-care and improvement aspect is evident. In a sense, meditation is self-mediation.

The Non-NLP ways of Self-Care

Let’s get out of the way the things that we can and should do by way of self-care that is not NLP related.

1. Get sufficient sleep

2. Exercise regularly

3. Attend to your food needs

4. Make time for yourself

And these things in and of themselves can already take you a long way. And if you were to search on the internet, there will be sites that list many more things that you can do to look after yourself. I have simply identified these four as fundamental.

Why NLP then?

NLP started off when its co-founders John Grinder and Richard Bandler modelled Virginia Satir (Systemic Family Therapist), Fritz Perls (Gestalt Therapy) and Milton Erickson (Clinical Hypnotherapy) and distilled the patterns of behaviour that allowed them to perform the therapeutic “miracles” they did. So in a sense, NLP had its beginnings in the helping professions and even today, NLP provides some of the more powerful methods of engendering personal development and change.

As a primer for the next entries to follow, I would like to briefly share with readers how NLP sees the interplay between Physiology, State and Representation.

Physiology

Physiology is fairly straightforward. It refers to our body; how we sit, stand, move, etc.

State

State refers to how we feel at any moment. These are the sensations we feel inside us; location, temperature, movement, etc. While it might be tempting to call these emotions, they are not necessarily the same thing. Emotions are the linguistic labels we have attached to the sensations we feel. Imagine as a child, you might have a sensation in your stomach region that feels tight, knotted and stuck. As a child, you would only know the sensation. You would have no words to describe it and would not know it as an emotion. You simply feel the sensation and it would manifest in your behaviours. Then an adult comes by, observes your behaviour and says “You’re feeling frustration!”. Now you have a word to describe how you feel. But it is important to realise that the emotional label is not the sensations that make up the state.

Representations

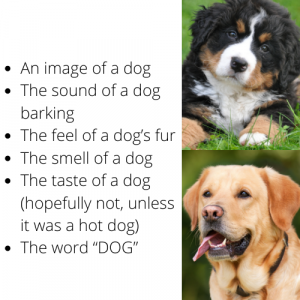

Representations refers to the way we represent the world inside our heads. Try this thought experiment. In a moment, not yet, I would like you to think of a “dog”.

In order for you to do that, you probably had in your mind:

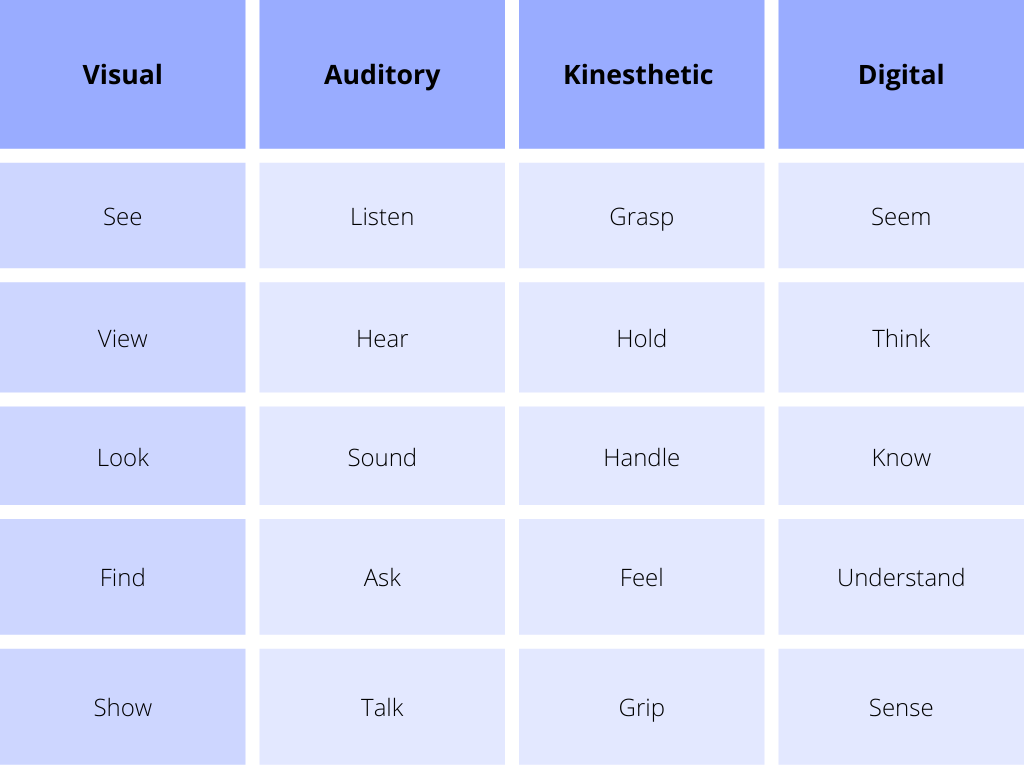

| Visual | An image of a dog |

| Auditory | The sound of a dog barking |

| Kinesthetic | The feel of a dog’s fur |

| Olfactory | The smell of a dog |

| Gustatory | The taste of a dog [hopefully not, unless it was a hot dog] |

| Digital | The word “DOG” |

You might have had only one of these or a combination of more than one. In NLP terms, we represent the world to ourselves in one of these six ways. The first 5 relate to the senses of sight, hearing, touch, smell and taste. The sixth way of representing the world is more meta, more digital and is more a label without connection to any particular sense. The word “DOG” has nothing to do with any of the senses. It is simply a label in much the same way that an “emotion” is simply a label for the sensations we feel.

In Closing

From NLP’s perspective, Physiology, State and Representation interact systemically. Put another way, when we experience something, our physiology, representation and state have to form a certain configuration. NLP posits that by changing one of these aspects of the configuration, we can change the experience. The easiest of these 3 aspects to change is actually physiology and we will explore how to do this in future entries. For the moment, a humourous illustration of this is Charlie Brown’s depressed stance.

This is not to say that we cannot alter our state or representations and this will also be something to explore in future entries.

I trust this gives us a good starting point to considering self-care and improvement in future entries. In the meantime, take care of yourself so you can take care of others!

To learn more about how Neuro-Linguistic Programming can help you, join us on the journey towards solving "The People Puzzle" - Prof Joel's flagship NLP training series. Obtain the blueprint to achieve greater self-awareness, enhance communication with others, and connect with people more effectively.

Unlock the People Puzzle today! 👉 https://peacemakers.sg/the-people-puzzle/